Dawson, New Mexico

In 1869, John Barkley Dawson who was once a cattle driver, pioneer, rancher and briefly worked as a Texas Ranger, journeyed to Northern New Mexico to the Vermejo Valley to homestead.

While there, Dawson found that this entire part of the state (and north into Colorado) was owned by a Mr. Lucien Maxwell. The land was part of the famous Maxwell Land Grant. Lucien was once the largest private landholder in the United States.

Becoming friends of sorts, Dawson paid Maxwell $3,600 and shook hands on a land deal that included a few thousand acres on some acreage 5.5 miles west into the valley from the settlement of Colfax.

By all accounts, Dawson led a fairly good life homesteading up the Vermejo Valley for ~15 years. It was quiet, safe and supplied could always be had down valley in Colfax or a little further away in Cimarron or Raton. Then in 1895 and 1901, something happened that would change Dawson’s life, he discovered coal.

At first, John simply burnt the coal for light and heat since it was of such a high grade. He also sold it to his neighbors. Lucien Maxwell sold some of his interests in the southern reaches of the grant in 1870. Shortly afterwards, word got out of John’s discovery and he eventually sold the land to a Mr. Charles B. Eddy for $400,000. The timing was almost uncanny. Dawson kept about 1,200 acres for himself and continued to ranch living out the rest of his days there in the settlement (and eventual town) that was named for him.

Tombstone in the cemetery

The miners section of the cemetery

In the far fields...

Two Italian markers

Old, disused tracks leading to/from Dawson

Eddy, who was a railroad pioneer from El Paso, Texas along with some business partners realized what they were sitting on. They formed the Dawson Fuel Company and put in a railroad to some of the burgeoning mines. Eventually, the railroad that Eddy built was stretched all the way south to Tucumcari.

In 1905, Eddy sold the land and the existing mines to the Phelps Dodge Corporation thus ushering in the golden age of Dawson. Wanting to expand the mines further and dig more tunnels, management knew they would need to entice workers to this part of northern New Mexico, basically isolated country. So they hatched plans to create a town to give employees a reason to stay.

Dawson at its peak, boasted almost 9,000 people. The town had a: hospital, department stores (including a Woolworth’s), movie theater, opera house, swimming pool, several churches, photo studio, bowling alley, a minor league baseball team and actual brick & mortar homes for their employees, not prefab shelters.

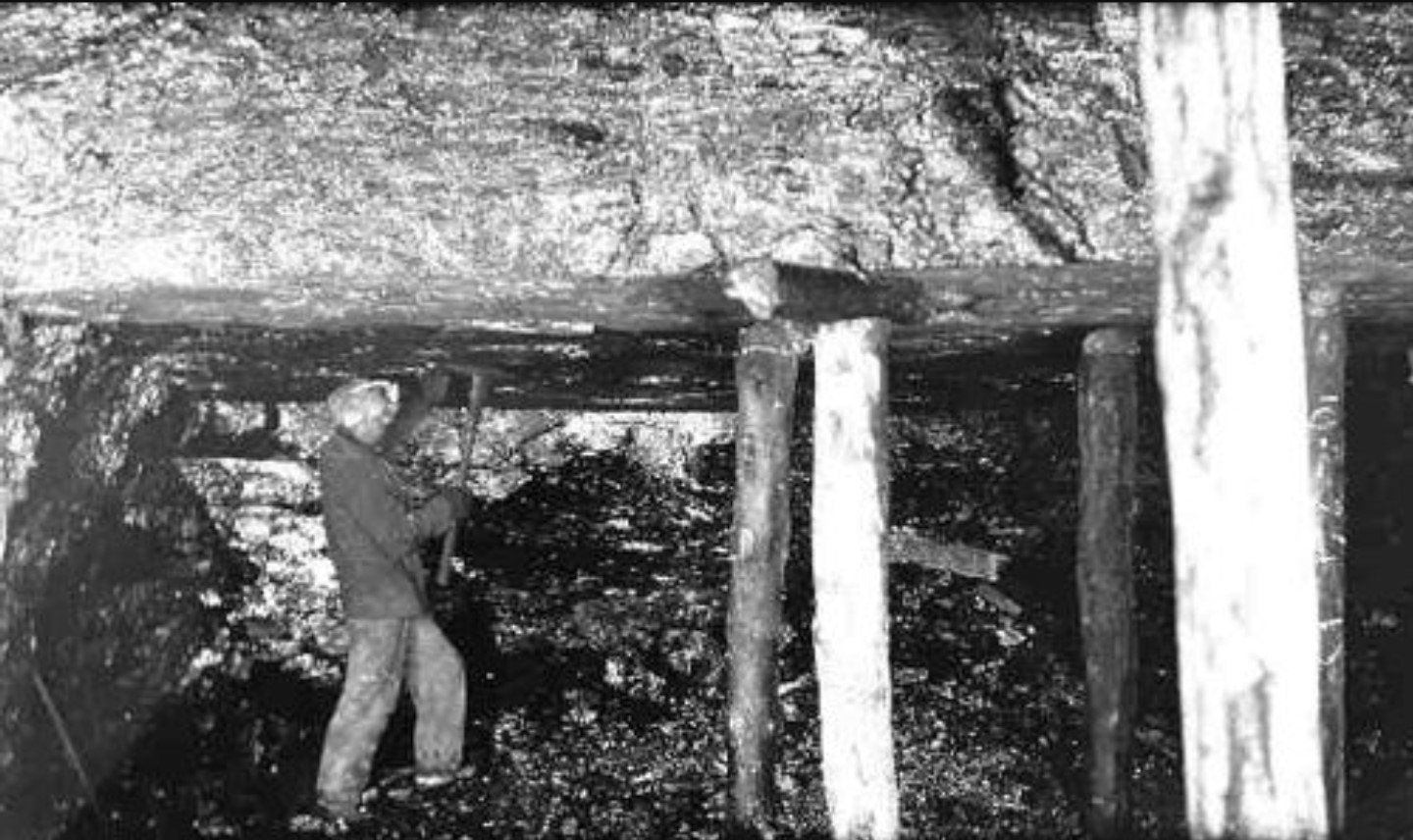

Most of the employees were immigrants from Greece, Italy and Mexico looking for employment that didn’t involve education, lengthy work records or references, blue collar, physical labor in other words. In all, there were ten mines in Dawson. The tunnels were usually referred to as Dawson Mine #1-#10 or Stag Canyon #1-#10. The mines were connected by an underground narrow-gauge railroad which ran all the way to the processor. Phelp Dodge sold railroad rights to the behemoth Southern Pacific Railways to take advantage of their infrastructure to move the coal out quicker. In the early days of Dawson, miners frequently died from black lung due to poor ventilation.

By all accounts, Phelp Dodge treated their employees quite well, a rarity in the early days of mining.

The first tragedy struck on September 14th, 1903, while the mine was still owned by Charles Eddy. A fire had broken out in Mine #1. Thankfully, 500 miners escaped. But it took almost a week to put the fire out. Three people died.

The second and largest tragedy struck Dawson on October 22nd, 1913. Stag Canyon mine shaft #2 exploded. The blast was so strong that it could be felt as far away as Rock Springs, Wyoming. Of the 286 men working the mine that day, only 23 survived, 263 miners died. It was later determined that a stick of dynamite went off during normal operating hours igniting airborne coal dust. Ironically, a week before the blast, a state mining inspector visited several of the mines stating that everything he saw was of top-notch quality and modern, especially the ventilation system. Although he did note a heavy presence of coal dust in the air.

Broken & forgotten...

Ruins from an old house

National Register

One of only two remaining houses in Dawson.

Slowly being devoured by time

Memories...

Maybe part of an old community house?

Ten years later on February 28th, 1923, a second explosion rocked mine #1. An ore cart ended up derailing knocking over some timbers. In the process, it severed a trolly cable creating sparks which ignited coal dust in the air. Of the 123 men who died in this explosion, many were children of those who had perished in the explosion ten years earlier.

On April 28th, 1950, the last carload of coal was dumped. Phelps Dodge shut down all production and closed the mines. Not because of the accidents perse, but because of a 25-year contract that Phelps had with Southern Pacific expired. Transportation costs without the contract had increased too much to make mining profitable. What the company couldn’t sell off outright was razed to the ground (and rather effectively at that).

On the evening of April 28th, most of those who hadn’t already left, gathered in the opera house to hear performances and drink themselves silly. Of those performing on stage that night, was a local miner named Augustine Hernandez. He sang a tune aptly named, “Adios, Dawson!”

The only structures left in Dawson are a couple of ruins on private property and of course, the town cemetery which, is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Coal mining deep in the ground. A dirty & hazardous job.

Main Street in Dawson, NM.

A current day coal cart

A railroad tipple in Dawson used to ferry coal to the processing plant.